At NJ Women in Data Science Conference, Princeton Prof Talks about Using Data Science to Study Sustainable Cities

NJEdge (Newark), IEEE Women in Engineering (Princeton/Central Jersey) and Verizon collaborated with Stanford University to bring the virtual Women in Data Science conference to New Jersey on Friday.

NJTechWeekly.com stopped in for a couple of sessions on this important topic. Data science pervades almost every type of research that companies and universities are doing these days, and New Jersey and its women have a big part to play in this.

Cohosting the event were Forough Ghahramani, associate vice president for research, innovation and sponsored programs at Edge; Rashmi Ketha, artificial intelligence (AI)/machine learning (ML) senior technical analyst at Verizon; and Vaishali Lambe, a consultant on digital practice, with specialties in advanced analytics, ML, AI and blockchain.

The first speaker was Anu Ramaswami, professor of civil and environmental engineering at the Princeton Institute for International and Regional Studies, and at Princeton’s High Meadows Environmental Institute. She emphasized the multidisciplinary nature of data science.

Ramaswami is not a data scientist herself, but she uses data science in many ways in her research as an interdisciplinary environmental engineer, she said. She spoke about using data science to study sustainable, healthy and equitable cities. In the U.S., more than 80 percent of people live in cities, and worldwide the proportion is more than 50 percent. Some 90 percent of the world’s GDP is generated in urban areas, she said, to set the tone for the talk.

To figure out how cities influence climate change, you have to look not only inside the cities, but outside of them, to where their supply chains come from and how they are impacting the planet, said Ramaswami. For example, she noted that by focusing on physical systems such as municipal water-supply, sanitation, transportation and food-supply networks, as well as buildings and public spaces, we can significantly lessen greenhouse gasses. But to do that, we need data.

She noted that people are at the heart of the problem. “People build infrastructure, people regulate infrastructure, people consume infrastructure and related goods and services.” We have to consider how people interact with all these systems.

So, to do this work, Ramaswami’s team needs fine-scale data on individuals and households, business policies, individual consumption, how individuals are responding to messages. “We also need information from social provisioning systems like healthcare and education.” Her group is interested in social justice and equity, as well. All of this data is exceedingly complex. “It requires not only what I spoke about, fine scale data, but also trans-boundary data,” she said.

Ramaswami gave some illustrations of the mix of data needed to create a true picture of what is happening. For example, in assessing carbon emissions directly over land, data scientists need to use a mix of satellites, planes, drones and other means, she said. “And it’s pretty complex because we have to separate fossil fuel emissions from biogenic emissions,” she added.

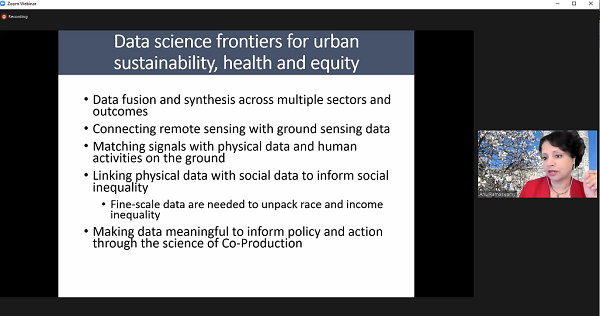

“The frontiers in my field of urban sustainability — where data science is just exploding — are in fusion and synthesis across sectors, outcomes and scales; connecting remote sensing with ground sensing; matching signals with physical data and human activities; linking physical data with social data to inform social inequality; and making data meaningful for policymakers.”

Ramaswami answered a number of questions from the audience at the end of the session. One question was on how to engage students and faculty in data science. She said, that if “we can be problem oriented, rather than driven by our own expertise,” that will open up new questions. Also, we have to learn things outside our own toolkits. That will stimulate collaboration. She also observed that students and faculty should have good quantitative skills, so they can pick up new techniques.