Eclectic Mix of Tech Professionals Mingle, Learn at 2017 Asbury Agile

Asbury Agile, a unique, entertaining, single-track conference for tech professionals and students, took place on October 6, a bright, sunny day at the Jersey shore. The venue was The Asbury hotel.

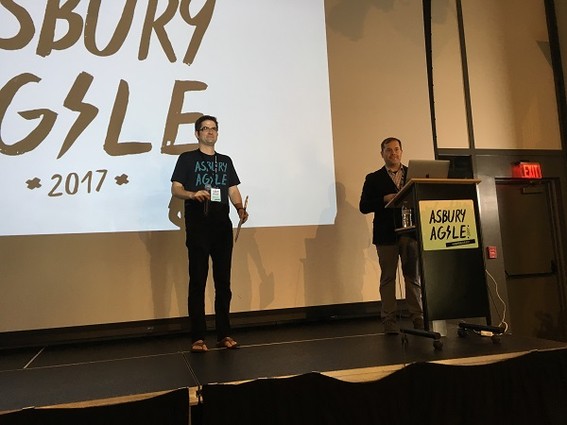

Conference founders Bret Morgan and Kevin Fricovsky welcomed more than 200 attendees to Asbury Park, noting that it was the seventh year the duo had put on this event.

The audience included a mix of UX designers, a front-end developers, a back-end developers, project managers, tech pros and students curious to learn about virtual reality programming or how to talk to an online audience like a human being rather than a robot.

There was an eclectic group of speakers with topics such as: “Write Once, Render Anywhere,” by Peggy Rayzis, an open source engineer at the Meteor Development Group (New York); “An Introduction to GRPC,” by Iheanyi Ekechukwu, a software engineer with DigitalOcean (New York); and “Designing the Conversation,” a talk about taking the babble out of online interactions with users, by Katie Giraulo, UX content designer at Capital One (McLean, Va.).

The first speaker, Tyler Hopf, creative director of IrisVR (New York), talked about designing for virtual reality. “VR is a ton of fun,” he told the crowd. “You can look at a mobile app or on a desktop, but rarely will you find an app that will make you start dancing. I’ve seen people scream when they put on a headset, I’ve seen people cry, I’ve seen people laugh.”

He noted that perhaps VR won’t be fully adopted, but there is “inherent power in stepping into a space and putting on a headset.” He called VR “the most physical of the digital technologies.”

“Virtual reality pulls from game design, architecture, software and cinema,” he said. You can see 3D objects and walk around them, he noted. “It’s really hard to do that with a desktop computer.”

How the heck do we know what kind of menus and tools should be built for VR, he asked the audience. VR has to mimic real-world interactions. In the real world, if you want to pick something up, you will reach out and grab it. In the desktop virtual world you may click on the object and drag it. “These are really different interactions,” said Hopf.

His team adheres to many rules when designing a VR product. One is that comfort is the most important thing. “We don’t want anyone getting sick. If someone gets sick, they will have a negative reaction. That means they are not going to like the game, they are not going to like the story, they will not like the building, no matter if it’s the best game, best story in the world.”

The virtual reality tools have their limitations, Hopf said. “You have to embrace the fact that some of the worlds might be a little less realistic. They are not going to have everything interactive. As designers and artists, we have to embrace that as a constraint.”

It’s important to put senses other than sight into virtual reality design, he noted. “To truly be immersed, you need to think about audio, you need to think about touch. … It really gives you a sense of being there, and gives the user more information about what they are looking at.”

After lunch, Mackenzie Kosut, global startup evangelist for Amazon Web Services (New York), talked about the history of how people controlled machines and computers. “If you think back over the years, how we interact with machines has changed quite a bit, starting with punch cards.” At the beginning, you had to interface with the machine on the machine’s terms. During the 1970s, he said, visual interfaces came along with drop-down menus with a huge number of options. We were pointing and clicking with a mouse or typing to make things work.

Chat was the next step in the evolution of interfacing with machines, and verbal chat is the most recent way in which people interface with machines, he said. It is natural and efficient. “You don’t have to go to an app or a website. You can just pick up a phone and start talking to your machine.” And you can interface with a verbal chatbot while you are doing other things, like driving a car.

Kosut said that AWS had decided to build Lex to create a standard and secure voice interface in a fragmented industry. Also, Lex is the core neural network behind Echo and Alexa. It’s been opened up to developers via APIs. Amazon integrates with some of the biggest enterprise systems, like Salesforce, so developers within companies can use the natural-language chatbot for their own customers, he explained. Since Lex is built on AWS, it also scales. “You can deploy one bot and you are ready to handle millions of users without extra effort,” he said.

Building a bot can be tricky, he noted. And he advised the group to start with intent. Even if you just want to build a bot to book a hotel room, there are many different ways someone might ask the bot to do that. Lex matches all the variations in utterances to the intent to book a hotel. In order to fulfill the request, there is basic information the bot needs in order to talk to the reservation system, such as the day, date, type of bed, number of people, and other check-in parameters.

Once the information has been collected, Lex interacts with the reservation system. “One thing about Lex,” said Kosut, is that “while it is really difficult to know all the different utterances a person might use to interact with the bot, what you can do is provide 10 to 20 sample utterances … and Lex will build additional ways someone might say the same thing.”

All the speakers at the conference were generous with their time, and they all answered questions from the audience.