Big Data Symposium: How Will Artificial Intelligence Change Higher Ed? Let Us Count the Ways

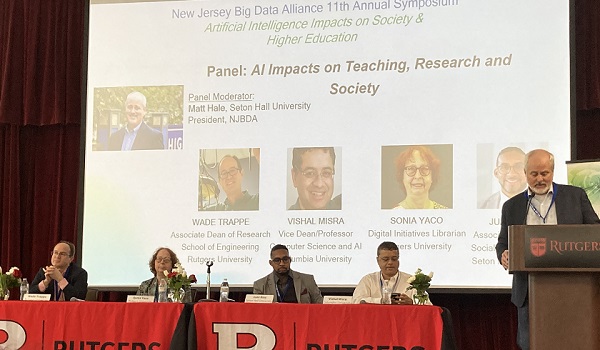

The 2024 New Jersey Big Data Alliance Symposium, held last spring at Rutgers–New Brunswick, focused on the impacts of AI on society and higher education.

NJTechWeekly.com dropped by a session called “AI Impacts on Teaching and Research.” The panelists noted that AI will change all aspects of college-level activities. As the panel introduction said, “Everything from grading to lecture formats to data collection, management and analysis will be changed because of AI.”

The panel was moderated by Matthew Hale, associate professor and chair of the Master of Public Administration program, Department of Political Science and Public Affairs, Seton Hall University. The panelists included Vishal Misra, professor of computer science and vice dean of computing and AI, Columbia University; Juan Rios, associate professor, Master of Social Work program, Seton Hall University; Wade Trappe, associate dean for research and development, Rutgers School of Engineering; and Sonia Yaco, digital initiatives librarian, Rutgers University.

Trappe began the discussion by noting that AI could be very useful to admissions administrators who are trying to create a cohort of students that will travel through the university together. For example, an administrator could be thinking, “I’ve got a whole bunch of athletes already coming in, but I need some artists and so on.” Trappe added, “You could really accelerate your cohort of students coming into the university admissions.”

Discussing another helpful aspect of AI, Trappe noted that the software will be able to create a list of faculty members who haven’t submitted grant applications in the last two years. That would allow deans to talk to them about it and help figure out how to accelerate the process. Trappe added that a tool called “Tableau” has those kinds of features and will soon be available to Rutgers faculty.

Misra noted that he is the first dean of AI at Columbia, and he took on this role after starting a company using ChatGPT-3. “At Columbia, there is a whole task force coming from the president’s office that is looking at all ways generative AI can help various aspects of the university. There have been 70 different use cases identified across the university, and we’re prioritizing which ones to take on first, from dining services to technology ventures, the licensing office to research teaming. We are also looking at helping researchers with pre-grant and post-grant processing.”

Probably one of the most interesting use cases for AI in higher ed came from Yaco, who deals in special collections. She noted that most American students cannot read cursive handwriting anymore because they aren’t being taught how. “I am working with a manuscript collection that has handwritten material. We have typewriter-written material, we have photographs.” There are collections, she said, with tens of thousands of photographs with no labels on them. And often there are illustrations in special collections. “Also, there are students who have different learning styles,” and they find it difficult to understand the material as it was originally created.

AI can solve a lot of those problems, she said. It can transcribe handwriting into typed text, and extract the text so that people can use it and all students can understand it. It can photograph typewritten material and describe it. “It can make what’s called a ‘MARC [MAchine-Readable Cataloging] cataloging record.’ You can decide if you want key words or if you want five paragraphs describing the photos. For example, you could say, ‘This is a photograph of a group of people that appears to be in 19th-century Korea in a rural setting.’ The AI can be phenomenally accurate, and you can link that text to a document that previously had no illustrations or text to photographs that previously had no text. You can link them together and make truly multimedia collections.”

Hale thought that AI would speed up research considerably. He remembered a research project on elections that he had done with his team earlier in his career. “I was looking at how local television news covers campaigns and elections, and to do this, we hired people in 50 television markets around the country to insert VHS tapes into their machines [to tape election coverage], pull the tapes out and send them to the University of Southern California, where we hired people to sit down and watch them and code them. We did this for the 2000 election. We did this for numerous elections. We have a lot of publications about it. And it took us almost a year to do every election, to do that process. I think it would be done in 37 seconds today,” he said, overstating the time savings for emphasis.

The next topic discussed was teaching AI, and Trappe had something to say about that. He pointed out that 18-year-olds already know how to use ChatGPT. “We need to teach them the guardrails. All right, when you’re using ChatGPT, how do you know that what you asked and what it’s giving you is not a hallucination? Do you know whether or not it’s fake, whether or not it’s built on all data that was fake? And, ultimately, it comes down to teaching them that just because some wonderful new tool tells you an answer doesn’t mean you should believe it, and that’s what we should teach.”

Rios gave his perspective as a professor of social work and public administration. “In one of my courses, I teach specifically around social policy. Often, we want students to understand how we begin to think about how our society looks from a divergent perspective. This is not just as the policy exists now, but what it can be, and so often our students are unable to stretch their minds, if you will. One of the tools that I’ve been integrating [into] the classroom now is the use of generative AI in the classroom to have students create scenarios, if you will, of a future if this social problem is addressed. So, let’s imagine, if you will, you’re working with a community who has been dealing with substance misuse. Can you create a picture of the future where substance misuse is no longer an issue, where homelessness is no longer an issue. Who have we worked with? Who are we working with? We start there from this image and from that image and are localizing it.”

He continued, “I’m at Seton Hall University, so, of course, I do a lot of work in the city of Newark, and we allow our students to localize how this possible future could look like in the city, in the community in which they live and serve. That’s an important piece here. … What is the distinction that we’re giving to our community based on all the stories that we’re talking about and all the AI tools that we’re integrating? How is the community benefiting from this knowledge now?”