Fairleigh Dickinson Expert Tells Morris Tech Meetup What’s Wrong with Polling

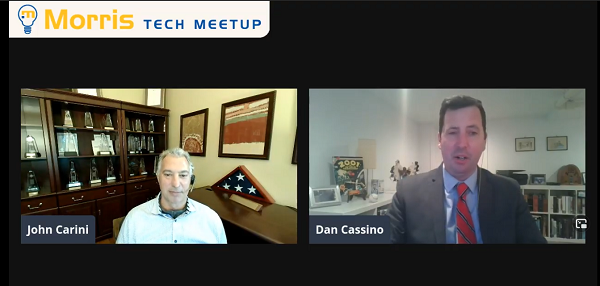

At a recent Morris Tech Meetup, members were treated to an inside look at political polling by Daniel Cassino, the executive director of the Fairleigh Dickinson University Poll. The video of the event can be found here.

Cassino describes himself as a political psychologist. “That means I’m a cognitive psychologist who studies how people think about politics, and how people think about the world.” He was interviewed by John Carini, one of the group’s organizers as well as the founder and CEO of iEnterprises, a Chatham-based company that makes intelligent customer-relationship-management software.

People often misunderstand the term “margin of error,” Cassino told the group. If “we were able to talk to every single person, there would be no margin of error,” he stated. But that wouldn’t be possible, and certainly not cost-effective. So, pollsters need to use samples, and samples have assumptions built into them.

Speaking about 2016, he noted that everyone should understand that the polls were not that far off, and that polling professionals predicted that Hillary Clinton would win the nationwide vote count, which she did. The polls were only about 2.5 percent off, which was within the margin of error, he said.

In 2016, there was some belief that Donald Trump’s supporters did not like responding to polls, he said. “If I call people up … then Trump supporters will be less likely to answer the phone, so the polls would be skewed against Trump supporters.”

“In 2016, though, the biggest problem we had wasn’t the nonresponse. It really seems like it was about less-educated white people. … When we called people on the phone, we were less likely to reach less-educated people. They’re less likely to pick up the phone.” The reason may be that they’re not at home as much, as they often work more hours or different hours, he said.

“So, the assumption in 2016, which was a good assumption at that time, was that less-educated white people and more-educated white-skinned people were going to vote the same. And it turns out in 2016, they didn’t. There was a huge gap there.”

Likely Voter Models

Polling professionals belong to a group called the American Association for Public Opinion Research, which concluded that in 2020 pollsters didn’t correct enough for this gap. Also, “likely voter” models are the Achilles heel of all election polls, Cassino said. It’s why Gallup doesn’t do election polling any more, he noted. “We have a problem. And that is when I ask you if you are going to vote, almost everyone says yes, and some of them are lying.” But if someone says “no,” they may be lying, too, he said. “So, we had to figure out some other way to determine who is going to vote and who isn’t. And various pollsters have their own secret sauce for determining this.”

In 2020, “We had no idea who was going to vote and who wasn’t because the voting system was all hacked up. Some people voted by mail, some people voted in person, or people who thought they would vote in person weren’t voting because they were scared to leave the house. So, we had no good way of knowing who a likely voter was.”

Pollsters had a decision to make: Do they trust everyone who said they were going to vote? “Well, if you do that, then you get results like we saw in Wisconsin that overestimated the vote.” Or pollsters could eliminate people who didn’t vote in previous elections, but that means they may end up underestimating the vote, he said.

In 2020, Trump did much better among young nonwhite voters, especially nonwhite men, than he had done in 2016. That was a big surprise to a lot of pollsters, but it’s something that most pollsters are going to miss, he said. “We’re going to miss it because there are factors that make you more likely to pick up the phone: if you’re white, if you’re older, and if you’re a woman. Therefore, the group we have the hardest time reaching is young nonwhite men.”

Technological Shifts

Cassino then recounted to the group some history of polling. Polling was invented in America in the early 20th century, he said, and there are cultural differences between countries that use the technique. For example, “in England, the response for telephone poles is very, very low, but the response rate for mail polls — we send you a questionnaire in the mail — is remarkably high. This, of course, is the opposite here. If I send out a poll via mail and I get 1 percent of the people to return it, I’m going to consider myself very, very lucky. In England, you’re going to see up to 70 percent response rates.”

The biggest technological shift in the industry has been away from landlines and towards cellphones; today most polls are 90 percent conducted on cellphones. This is a problem for pollsters because of a regulatory issue in the United States. The federal government doesn’t allow pollsters to use auto dialers for cellphones, so they must use other technologies.

The meetup group wanted to know why pollsters don’t use Facebook or Twitter to conduct their polls. “The problem is that the people who use Facebook are not a representative sample of the public as a whole. And, so, I can’t learn about the public.” Cassino said that when he uses Facebook data, he only learns about the people who use Facebook.

SMS text messaging has become popular. “So, instead of calling your cellphone, I just text you and introduce myself, and people are more likely to respond to that than they respond to telephone inquiries because, you know, it doesn’t feel like as much an invasion of privacy.” However, it can’t comprise the entire poll, as text messaging is less likely to reach older people.

Cassino added that some pollsters who try to discover the attitudes of niche audiences will put polls on apps that are designed for those audiences: for example, an app that is only used by homosexual men when pollsters are trying to reach that group.