Remote Learning Failed Vulnerable Populations, Panelists Say

In a web conference convened by the cofounders of Wayne-based ConnectYard, CEO Donald Doane and COO Grant Muhoozi Warner, panelists discussed distance learning and racial justice.

This webinar, the first of a planned series by the educational technology company’s Black Learners Matter initiative, focused on identifying the problem. You can find the video of the web conference here.

The bottom line: Remote learning has failed the most vulnerable of our populations, who are mostly Black and brown.

The reasons are complex: the lack of internet-ready devices; lack of access to Wi-Fi or even broadband; lack of experience with technology, so that even getting connected or accessing Google Classroom is a mystery; households with multiple students or social problems; and institutional racism.

The panelists for this program were: Neal Reich, assistant principal of the Young Adult Borough Center, at Abraham Lincoln High School (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Reverend Alfred Cockfield, founder and executive director of the Lamad Academy Charter School (Brooklyn, N.Y.); Demond Pearson, senior program director at Good Shepherd Services (New York); and Michelle Henry, a parent of a 6th grader at P.S. 109, in Brooklyn, N.Y. Warner moderated the event.

The panel opened with a 26-second “moment” of silence for George Floyd and all the others affected by racism and police brutality.

Unequal Impacts

Saying that we are “all in the same storm, just not in the same boat,” Warner noted that the pandemic has had a more severe impact on the Black and brown communities, which have a COVID-19 death rate that’s twice the rate for other populations. “This got us started thinking that this was the visible impact of COVID. What was the invisible impact?” He noted that Black and brown students were already lagging behind in educational achievement when they had a teacher in a classroom. What would happen to them when there was a sudden switch to remote learning?

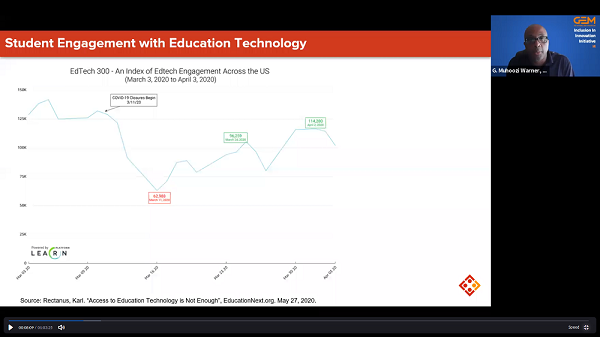

Warner noted that schools have structural problems that have their origins in the days of “separate and unequal.” The disparity “is driven in part by school funding formulas which are dependent on property taxes,” said Warner. The bottom line is that, while most students have access to educational technology, the “haves” are using that technology more now, and the “have nots” are not being included, he said. The “have nots” are usually students of color.

Citing an example from the Detroit area, Warner noted that Detroit’s public school system receives local funding of $800 per student. Grosse Pointe, a local suburb, gets $5,000 per student. “That’s not a gap that the federal government closes,” and this situation creates persistent problems. “But it’s not just funding, it’s also policy.”

He noted that one of the really shocking things “as we started on this path of discovery, trying to understand what was happening in K–12 under COVID,” was how little synchronous instruction was actually happening. According to the website Easy LMS, “Synchronous learning refers to a learning event in which a group of participants is engaged in learning at the same time. For that, they should be in the same physical location as a classroom or the same online environment, such as in a [web conference], where they can interact with the instructor and other participants. There is real-interaction with other people.”

A Mother Speaks

Remote learning created new challenges in the life of one panelist, the mother on the call, Michelle Henry, who lives in a family shelter with her talented son. When school closed on March 16, her son had to be with her all day in the shelter. The school had given the students laptops on which to do their work, but her son was unable to use it because there was no internet in the shelter. She reached out to the school, but it took two weeks for her son to get a tablet with integrated internet. And Michelle was frustrated because she didn’t have any idea how to set it up.

When she contacted the school again, they told her that they were going to upgrade the tablet and put everything into Google Classroom. And they did, but that’s “when I got bombarded with assignments. I had no idea how to submit work, or how to get in contact with the teacher.” The teachers kept calling her, complaining that her son wasn’t doing the work. The problem became more critical, especially as teachers and coordinators didn’t take the time to explain the system to Michelle; they instead told her son to do the work on paper, take a picture of it, and submit the photo. She was especially frustrated with the math homework, as she both had difficulties with the subject matter and with the process of submitting it. “I felt all alone,” she said, and she worried about how she was going to help her son.

Michelle didn’t give up. She figured it out, but the experience was excruciating, and her son lost a lot of time that he could have been using learning.

Too Many Platforms

Reich, who deals with an at-risk student population of 17- to 21-year-olds who don’t have enough credits to complete high school, said that his school had created packets for its students with information on how to get on the internet, how to hook up to Wi-Fi and how to sign in to Google Classroom. The staff and teachers tried to upload assignments within three days, to move students forward, he said. They started with Zoom, he noted, but went back and forth between Zoom and Google Classroom. Some of the challenges came from the lack of software at the school and the staff’s own knowledge gaps; after all, remote learning wasn’t something they ever thought they’d need to prepare for.

He regrets that the teachers and staff couldn’t be there for the students in the aftermath of the George Floyd murder. He said that they didn’t have the platforms or software to do this remotely. Also, his students are parents or taking care of families, or they’re working people. “I can’t get everyone online at four in the afternoon.”

It’s also frustrating that distance learning has so many different platforms, said Reich. Some schools use Microsoft Teams, some use Google, some use Edmentum, some use Apex and some schools use something else, so “you can have five different platforms to learn in one household.”

COVID-19: A Disease of the Community

Cockfield’s Lamad Academy, in central Brooklyn, is aimed at middle schoolers who could be two or three grades behind. The school has just started this summer, but Cockfield also has a Christian school that serves children from pre-K to sixth grade.

“It took us a while to get up and get going. But one of the things we did was make sure that our children had” packets of materials “while we prepared to go online.” Cockfield said that he had heard from a lot of parents that for some districts everything was fine from day one, but for others nothing was in place, and they still “don’t have access to that tablet today.” There is so much disparity, even in 2020, he said.

Pearson noted that the lack of Wi-Fi put his students at a disadvantage, and he asked, “Who is the IT department that the family can go to when the device wasn’t working?” Many parents don’t understand the technology, he reiterated.

But his biggest point was that COVID-19 was a disease of the community. He explained that educators have to take into account the social and emotional needs of the whole family, not just the student’s educational needs. One major problem is that food insecurity got worse once the schools were no longer feeding their students. Also, according to Pearson, people don’t realize that schools are safe havens for some populations, and that schools have to deal with the whole child, including the child’s home environment.

For example, is a student going to be able to complete her online work if she’s one of several children in a two-bedroom apartment? She has to share resources. And when can she be alone in a room, so she can concentrate on the lessons? In addition, there may be alcoholism, domestic violence and drug abuse.

Teachers are usually the first focal point for students who are at risk, but school staff had to find alternative means of reaching students during COVID. Sometimes teachers or counselors were texting their students just to keep in touch or to find out if there was food in the house or if there were other problems that needed to be addressed, panelists said.

At the end of the event, Warner noted that the next part of the discussion would address some of the solutions to these problems. The next webinar, entitled, “Black Learners Matter: Our Collective Responsibility,” will be held on Wednesday, July 22, at 4 p.m. ET, and would be led by a panel of equity experts and thought leaders, including Lisa Love, cofounder of Tanoshi (Oakland, Calif.), a Shark Tank winner; Ash Kaluarachchi, cofounder of StartEd (New York) and producer of EDTECH WEEK (New York); and William Crowder, entrepreneur in residence at Morgan Stanley (New York). You can register for the event here.