Stevens Students Design Computer-controlled Drone to Detect Underwater Explosives

Last spring, the United States Department of Defense presented a team of students at Stevens Institute of Technology (Hoboken) with a challenge: an estimated 30 million pounds of explosives lie submerged off the coast of the United States. They need to be disarmed.

Since then the students have been trying to help solve that problem by designing and building an underwater drone to detect those explosives so that authorities can dispose of them safely.

The students – mechanical engineers Michael Giglia, Joe Huyett and Mark Siembab; computer scientists Ethan Hayon and Brandon Vandegrift; and naval engineer Don Montemarano – worked together for the Perseus program, which is a design contest sponsored by the Defense Department’s Rapid Reaction Technology Office. Several of the students participated in part to fill the Stevens requirement that all seniors complete a design project.

Students demonstrated the drone for the public and press in late January at an event on the Stevens campus.

Professor Michael DeLorme, who is a research associate at the Center for Maritime Systems at the Davidson Laboratory on the Stevens campus in Hoboken, served as the students’ faculty advisor. He helped recruit the team, but otherwise he stepped aside and let the students work from scratch.

“This is all their design,” DeLorme said. “The Defense Department gives them a problem, but then it’s up to the students to figure out how to solve it.” DeLorme said that the government runs programs like Perseus to compare student design ideas with ones from professional defense companies.

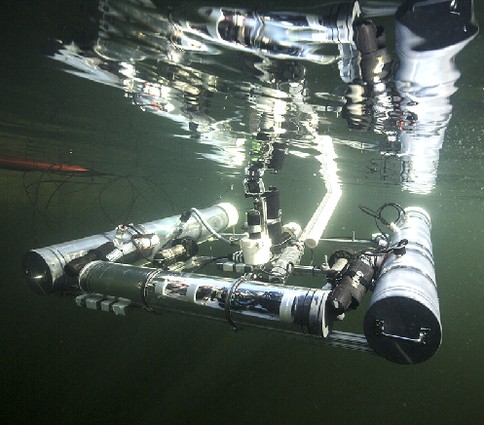

The 48- by 38- by 16-inch, 70-pound, H-shaped drone has an aluminum frame that supports sealed tubes carrying electronic equipment. The drone’s thrusters allow for a full range of motion, and its several sensors include sonar, magnetic metal detection, a laser dimensioning system, and three high-definition video cameras.

The drone is tethered to a buoy on the surface that sends information back to the team on shore, which can watch and control the drone remotely through a computer screen. Once the drone locates an object, its sensors can determine the object’s dimensions and composition. The drone’s computer then checks the information against an extensive database of explosives.

A typical scenario for using the drone might involve a civilian boat encountering an unknown object underwater but close to shore. Authorities could then use the drone to inspect the object, sparing human divers potential danger. Although many objects underwater are harmless, hundreds of unexploded bombs, mines, missiles and other weapons litter the American seaboard. Some come from military training exercises and others from actual wars, especially from World War II, and even as far back as the Civil War.

DeLorme said that weather forces such as hurricanes can cause enough soil erosion to unearth previously buried explosives. He added that the drone could have other uses besides detecting explosives, such as environmental monitoring or offshore oil drilling. “It’s a huge field,” he said, comparing the drone to a versatile pickup truck.

The students built the drone over nine months with a $15,000 grant from the government. Many of the parts are common objects such as a video game controller that moves the drone. The drone’s surface equipment rests on a fluorescent boogie board more commonly used for surfing waves.

This is the fourth time that Stevens has designed an underwater vehicle for the government and the second year it has participated in the Perseus program. Like the students last year, who built a drone to detect an underwater communications cable, the students this year participated in a demonstration in Florida that also included students and drones from Florida Atlantic University, Georgia Tech, North Carolina A&T and Florida Keys Community College. The Stevens drone passed the government’s demonstration test of being able to operate and detect successfully while 40 feet underwater.

The students said they learned to overcome many challenges during the project, including working under budget and managing their time alongside classes. They solved a major problem just before the Florida demonstration that involved waterproofing the drone for ocean levels of pressure and salinity after they previously had only tested it in the Davidson Laboratory and the Hudson River.

Montemarano, a naval engineering student who plans to join the Navy after he graduates, said he and the other team members learned how to blend together their various areas of expertise. “We took it step by step, and we each asked what we could do to contribute,” he said. “There were times when we all had to be Johnny on the Spot.”

Huyett said the students had to remember to focus on both higher and lower levels of design. “We could design the most intricate vehicle, but if there’s a problem with a simple 5-volt battery, then it’s not going to work,” he said.

Although the Stevens students worked on the drone through their school, the project also has an entrepreneurial aspect. Huyett, Montemarano and Siembab pitched the project as a startup within Stevens’ Technogenesis program, which teaches students about entrepreneurship. Montemarano said that pitching to investors helped the team better understand the project. “We had to think how to explain this to people who aren’t engineers,” he said.

DeLorme said he thought the students learned to give a very polished pitch. “People thought they were from the government,” he said.