During Newark Tech Week, Panel of Diverse Women Talk About Startup Founder Challenges

Newark Tech Week 2021, sponsored by Invest Newark and the New Jersey Economic Development Authority, and presented by =SPACE, a coworking facility in Newark, took place in December.

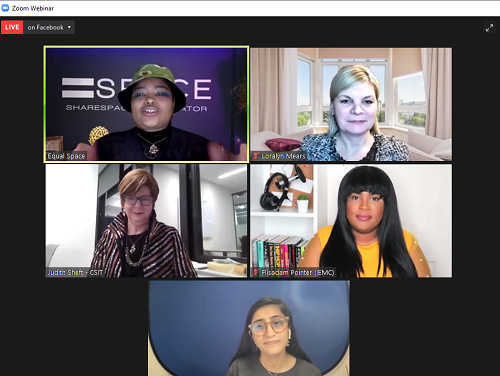

In one of the sessions, Loralyn Mears, founder and CEO of STEERus (RiverVale); Judith Sheft, executive director of the New Jersey Commission of Science, Innovation and Technology (CSIT); Anum Hussain, cofounder and CEO of the Below the Fold newsletter (San Francisco); and Flisadam Pointer, editor-in-chief of the independent music news site ENVERT and executive director of the Independent Entertainment Media Coalition, discussed challenges to women and people of color in tech on a panel moderated by Kelly Outing, community manager at =SPACE.

After she introduced the panel, Outing’s first question went to Judith Sheft: “What does it mean to be a woman in the tech industry to you?”

Pathways to Tech Careers

Sheft explained that she came from a family of scientists. Her father was a chemist at several federal laboratories and her mother had been a nutritional chemist before she stayed at home to raise her children. “I always knew that there was a pathway to work in the science area. I just had to figure out which field made sense to me. I became a mathematician partially because I like to be able to do my work anywhere.”

She noted that not everyone comes from the same place that she came from, with ready-made role models at home. Over her career, Sheft said, she tried to be helpful to others and reach out to young women, to become a role model and really be present for them.

Hussain said that she came from a family that was not in tech, and she fell into the industry by accident. “I was studying journalism and getting calls from tech companies to work on their blogs. And I say that because I think sometimes we need to be told” to ignore the idea that people have to have background knowledge or experience in tech. Women can come into the tech field with different strengths, and find a place for themselves, she said.

Pointer’s path developed in a different way. “So, for me, I didn’t realize that tech was a passion of mine until I found out how integral it was to creating interactive experiences and live performances. So, when I started in tech, it was essentially ‘how do we get tech to assist with the storytelling that we’re doing here at an in-person event?’ For me, the way I define being a woman in tech is essentially being open and being receptive to innovation and how you can use something to elevate, or as an addition to complement what it is that you’re working on, whether that is via the form of event promotion and planning, or a digital storytelling by way of a magazine or blog site or a podcast.”

Adding to the conversation, Sheft noted that “There are some people that might like to build the infrastructure, develop the hardware, develop the computer languages; and then there are other people who are going to be in tech, and they’re going to use those tools in areas that are of interest. … So, I think technology is really a language that everyone needs to be able to figure out ‘how can I use it to work on the things that I like to work on?’”

Mears recalled that she went right from her graduate studies to Sun Microsystems ( Menlo Park), which she recalled was a very progressive place with the most amazing people she had ever worked with or worked for. “When I worked there, there was no kyriarchy. It didn’t matter if you were black, brown, female, this or that. You were just there, and you brought ideas forward, and you were respected and represented and you were heard.”

However, when she went out to conferences, things were different. Women weren’t respected or given a voice there. “What I’ve done is recognize that there are not enough of us gals in tech. So, even my podcasts right now, it’s all to shine the light on women who may not have as much of a voice, and that’s the kind of thing that I want to be able to do, so that we do have a forum and can support each other.”

Outing asked Mears how she figured out how to build STEERus, a platform that teaches soft skills, into a business that would help others develop their voices. Mears said that she saw the need for the platform all around her, in her stepchildren and in her friends’ children. People were afraid of constructive criticism, and they badly needed to learn the soft skills. That grew into something more aspirational, she said, as she expects STEERus to be “uplifting diverse people and underserved communities who are finally getting access” to jobs because we will be “a driving force behind equity in career and talent development.”

Lessons Learned And Challenges

Outing also asked the panel to tell her their biggest lessons or challenges so far. Mears said that she went into beginning a startup very confident that she could do everything at once, but she has been “humbled to the core.” She added, “You have no idea what’s really involved. You can read all day long, but it’s totally not the same as setting up all of the legal this, finance tax that, and corporation stuff; building an executive team, building a board, building a community of coaches, creating an online software platform and creating a content library. As it turns out, that’s too much to take on at one time. So, to any other entrepreneurs out there: Do it one at a time. I definitely am.”

Hussain noted that for her, the biggest challenge was in fundraising. “We raised money, but pennies compared to what other startups do and what we need. And so that was a very challenging experience to walk in and be the expert in what we’re doing” and see “how people just question it over and over and over again. And then, to even have your highest opportunity investors stringing you along.” It was frustrating because she “literally didn’t know where I was going to get the payments” for her team. This was ultimately one of the reasons why her team is now part-time, she said.

The lesson Hussain learned from all this was to stick with her vision and believe in herself. In those early VC conversations, she was pointed in different directions by different VCs, she said. “And then you learn that VCs are not necessarily the smartest people in the room.” They are not the experts, and they don’t know what it will take for you to reach your audience, she added.

Sheft talked about CSIT, which focuses on the super early-stage innovator. She emphasized the importance of the state having personal contact with the very young entrepreneurs here who need the agency’s services, especially women and underrepresented entrepreneurs. Besides giving out grants, CSIT wants to make connections between the early-stage innovators and the research universities, where there may be people, advice and equipment they can use to advance their work. “We want to help facilitate those conversations.” She noted that part of her role was to give the innovators some of her own confidence and help point them to other resources that can help them. She said she is happy to talk to anyone and lend them a hand.

The biggest piece of advice she wanted to pass on to entrepreneurs is not to care what other people say. Focus on what you are trying to do, ask a lot of questions and keep moving forwards, she advised. Sheft then noted that one of her favorite quotes is, “When you reach the top of the mountain, keep climbing.”

Outing asked Pointer about how journalists are merging tech into their work. She answered that during the pandemic, journalists began to use tech in more innovative ways to enhance creativity. Pointer believes that journalism is often a step behind the tech industry, embracing new technologies after they have already passed by. She is trying to change that by using tech creatively in her organizations. The Independent Entertainment Media Coalition offers a summer program for high school students who have expressed an interest in interning in journalism, including podcasting or video journalism. It is revamping the program to take accessibility into account, as not everyone can get to their physical location, “We want to create a virtual reality space for these educational experiences,” so that students with ailments or mental issues can still have access. Pointer envisions the space to be similar to what Facebook is doing with Meta.