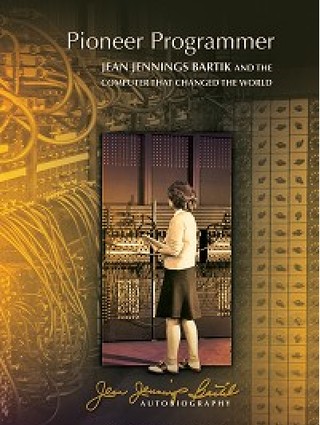

Book Review: “Pioneer Programmer: Jean Jennings Bartik and the Computer that Changed the World”

I recently finished reading the autobiography “Pioneer Programmer: Jean Jennings Bartik and the Computer that Changed the World,” and I highly recommend it.

It’s a terrific firsthand account of the early days of computing, and it’s true to Bartik’s personality. In life, Bartik never sugarcoated a thing; she told it like it was. And in her book she does the same.

According to Bartik, John von Neumann didn’t have as much to do with the development of the computer as he professed to (Chapter 1); Grace Hopper, who is revered in the history of computing, had a drinking problem (Chapter 5); and, most important, in Bartik’s view — supported by others, many documents and Bartik’s own keen observations — ENIAC designers J. Presper Eckert (whom Bartik called Pres) and John Mauchly were robbed of their patent rights (Chapter 7).

ENIAC, which stands for “electronic numerical integrator and computer,” was a parallel processor before that device had a name. It was a programmable, general-purpose computer, not just one that could perform the specialized task for which it had been created.

Bartik’s descriptions of events that occurred during the development of ENIAC make you feel as though you are right there in the room with her. A demonstration had been planned for February 1946 to demonstrate that the ENIAC could calculate an artillery shell trajectory faster than the time it took a shell fired from a gun to trace it. Previously all such trajectories had been calculated by hand by women called “computers,” which took many, many hours.

The programmers worked day and night to prepare for the demonstration. However, a bug in the program made it seem as though the trajectories were continuing to travel after they had hit the ground.

Betty Snyder, who was said to be able to solve problems in her sleep, came up with the needed programming change right before the demonstration. She and Bartik made the changes, and the demonstration went off without a hitch. Yet the female programmers weren’t invited to the celebratory dinner. The women who performed the ENIAC demonstration that historic day were thought of as models — not unlike the appliance models of their time — who had had nothing to do with the machine.

Decades later, in a February 15, 1976, article, the Philadelphia Inquirer would call ENIAC “the machine that changed the world,” Bartik noted in her autobiography. It took the ENIAC women many years to be recognized for their accomplishments. We can thank Kathy Kleiman, historian and founder of the ENIAC Programmers Project, for that.

Let me say that I couldn’t wait to read Bartik’s autobiography. The reason: Jean Jennings Bartik was my boss and mentor at Auerbach Computer Technology Reports (Pennsauken) when I first started writing about computing in the mid-1970s.

Bartik was a terrific boss to have. I must have thanked her a million times for teaching me, a journalism major, to love both computing and the business of computing. I also admired her patience, overall teaching ability and unyielding support for professional women.

After reading this book, I know that Bartik’s patience and teaching ability resulted from her experiences with Pres Eckert and John Mauchly, whom Bartik says were not only brilliant and inventive but good, honest men. They took all the time needed to explain and teach the concepts that newly minted programmers needed to understand this machine. “No question was too small to ask,” Bartik says of Eckert.

Bartik was passionate about promoting women in the workplace. I can still hear her voice and remember what she told me when while at Auerbach I learned that a male editorial assistant with less experience was making more money than I was. I remember asking Bartik what to do, and she advised me how to handle the planned meeting with her superior.

I went into that meeting armed with great arguments for a raise but came out with no more money than I was paid when I walked in: the manager told me my male colleague had “more potential” than I did.

I started looking for a new job then and left Auerbach shortly thereafter to become the minicomputer editor for Computerworld, which in those days was at the pinnacle of its success. Bartik cheered me on, literally. She was delighted that I was able to leverage my experience with her for my new job.

What I didn’t realize at the time was that Bartik was facing her own struggle with the glass ceiling in the workplace (Chapter 6). While she spent a long time in the computer industry — much of it in New Jersey, at Auerbach — she was unable to make it a lifelong career. She could never be promoted to vice president at Auerbach, despite knowing Isaac Auerbach personally and professionally. In the book, she recounts how she tried to file a suit on behalf of female workers at the company but feared losing her job.

Bartik’s pioneering programming work took place in Philadelphia, but she was a New Jersey resident. She lived near the Jersey Shore in the late 1970s for a while when she worked at Interdata, a minicomputer company in Oceanport. After her years at Auerbach, she resided in an apartment complex in Oaklyn, New Jersey, with a view of Philadelphia from her window, her son Tim told me. I visited her in some of those places.

I didn’t know much about Bartik’s background before reading “Pioneer Programmer,” except that she came from the Midwest and traveled to Philadelphia after accepting a job there. She had applied for it after seeing an advertisement for math majors who wanted to help with the war effort. I have never met her children, but I have kept up a bit of a Twitter conversation with Tim, who is an economist.

I’m certain that growing up in a large farm family helped to form Bartik’s personality and forge someone who needed to be assertive just to be heard. In addition, her family had great respect for intelligence and learning.

Bartik never hesitated to express her opinion, and she always let everyone know when she had a contrary view. I had to love and admire this woman. Read her book, and you’ll love and admire her, too, for her outspokenness and her honesty.

[As Jean would have wanted, all proceeds from the book will go toward the Jean Jennings Bartik Women in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics Scholarship.]