Princeton Professor Brings 3-D Audio to Princeton Tech Meetup

A technology that can allow you to listen to a recording and hear every instrument in an orchestra as though you were sitting in an ideal sweet spot in the audience was demonstrated at the Princeton Tech Meetup (PTM) in September.

At the end of the meeting, PTM members were able to take turns hearing “3-D” audio music in a way they had probably never experienced before, except in a concert hall.

The speaker was Princeton University Professor Edgar Choueiri, an avid audiophile, acoustician and classical music recordist. He has pursued a decades-long passion for perfecting the realism of music reproduction.

“I wanted to give you a feel for this field, which is driven now by virtual reality and augmented reality. But the reason I got into it is I’m a frustrated musician. I love to play classical guitar,” he told the group. However, he said he found that he wasn’t very good, so he began recording musicians live. For many years he recorded the university’s symphony as a hobby.

“I found something very frustrating,” he said. “You can record an event, with very good equipment, and come home and listen to it. You can get very good tonal fidelity. The sound sounds very real from the tonal point of view. … What has been lacking is ‘spacial’ fidelity, getting an orchestra to sound like an orchestra.”

The PTM meets every month at the Princeton Public Library. As of the last meeting, it had 4,500 members, according to Venu Moola, organizer and host. In fact, the 4,500th member, a fellow named Glenn, was asked to help show how the technology works.

To demonstrate 3-D sound, Choueiri had Glenn sit in a chair equidistant from two speakers, and gave him an ear device. He first showed Glenn how a single bird chirping would sound from outside a window, and then from right by his ear, as though the bird were on his pillow while he was lying in bed. Then Choueiri used a recording of group of people chatting, who sounded as if they were somewhere near where Glenn was sitting. Glenn pointed in the different directions from where he heard voices, saying that some voices sounded closer than others.

The localization of sound is important because it has an emotional impact, said Choueiri. It can portray a natural, bucolic scene. But it could also give you information when you’re driving. Imagine what it would be like, he said, to hear the phrase “turn left” coming from somewhere to the left of you.

When musicians compose music, they are involved with multiple dimensions such as melody, pitch and timbre; but they generally don’t consider spacial localization. Being able to do so will give their music additional depth, Choueiri said.

In fact, choral music composers have been trying for years to figure out how to use localization in their compositions, and while they sometimes succeed in concerts, they have not been able to succeed when recording or in other situations. Several have tried by writing songs for many different voices, with the voices echoing each other.

Surround sound is not really 3-D sound, Choueiri said, because it is not an accurate positioning of sound in space. In order to make an accurate representation of 3-D sound, scientists have to understand psychoacoustics, or how humans perceive sound.

There are three types of cues that the human brain uses to locate sound, he said. One is ITD, or interaural time difference, which is the different amount of time it takes for a sound to reach each ear. The brain, he said, is very astute at measuring this very small time difference.

Another is ILD, or interaural level difference. Sound may be a little louder or softer in each ear, depending on what side of the hearer it comes from; and the brain analyzes that level.

However, humans can still recognize whether a sound is in front of them or behind them, even if the IDT and ILD are zero, he said. That’s because of the third cue: they can sense the harmonics that interact with the outer ear.

All of this is very similar to the way 3-D glasses work, he explained. The differential information caused by the distance between the right and left eye is needed for humans to see in 3-D. “But it’s important that the right eye does not see the left image and the left eye does not see the right image.

“That wall between images is immensely important. In fact, in my invention, which is now the third most successful invention in the history of Princeton, all I’ve done is create this little wall.” However, his “little wall” consists of sound pressure.

It is created through a process called “destructive interference.” “Essentially, I am sending the same sound, but upside down.” This interference will cancel out the sound, preventing it from reaching the wrong ear. “The filter sends negative and positive waves precisely timed to arrive at Glenn’s ear and cancel all the sound that comes from the right speaker to the left ear.”

He noted that others had worked out the problem of sound cancellation, but when the filters they developed were tested, the music sounded “horrible.” The price of using these filters was tonal distortion, he said.

“My contribution was that I found a way to design filters with no tonal distortion,” said Choueiri. “I got lucky,” he added. “It was purely a theoretical mathematical solution before I did any experiments.”

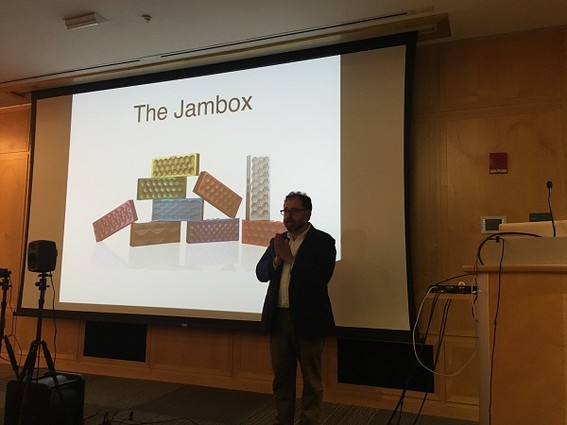

Choueiri explained the math and analytics he used to solve the problem, in depth, to the technically minded PTM audience. Princeton University has licensed his invention, called “BACCH 3D Sound,” to some manufacturers specializing in high-end sound equipment and to Jawbone (San Francisco, Calif.), which then developed Jambox wireless speakers based on the technology.